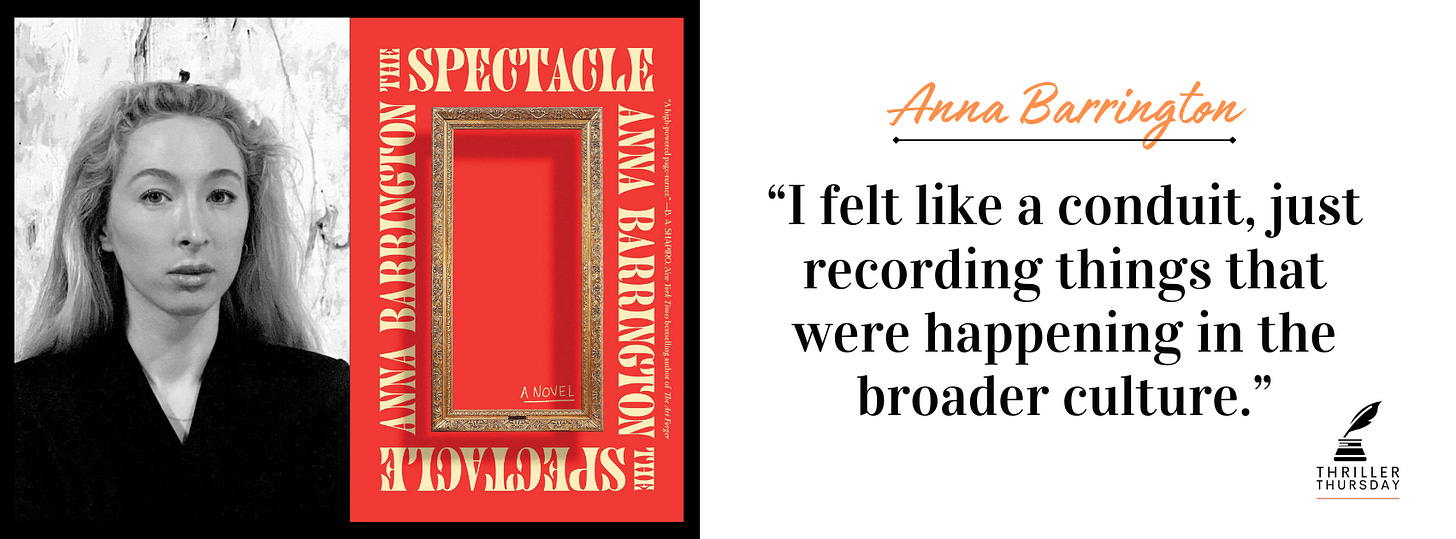

Anna Barrington is the author of The Spectacle. She has worked in contemporary art galleries, museums, and auction houses for seven years. She received an MA from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London and a BA from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. Barrington grew up on Cape Cod and currently lives in the UK. The Spectacle is her first novel.

The Spectacle is out now!

The Spectacle delves into the dark underbelly of the art world—a glittering facade that hides scheming dealers, pretentious artists, ruthless collectors, and a mounting web of debt. It’s clear you didn’t just stumble into this world, but know it intimately. What experiences shaped your understanding of this exclusive, high-stakes scene?

Everything in The Spectacle comes from my own experience. I worked in galleries and auction houses for years, going to those parties and listening to those conversations, before the idea for the book appeared. People created their own myths from nothing with varying degrees of success. Because the price of objects was so abstract, and in certain ways unrelated to how good an artwork was, you saw this tension. People instinctively understood that the price of things was arbitrary, and they applied the same philosophy to their personal brands. There was a great feeling of irony and fun. My friends and I would say all the time it’s all bullshit, but to a client, that’s another thing.

I was both within and without because I was observing. I would go to parties and then go home and take notes. And, as the political situation changed, I started thinking of how the art world felt like a dark mirror of America in that moment. Larger issues that the country was grappling with would get absorbed very quickly into the art world’s nervous system, and you’d see people’s immediate reactions—sometimes funny, cruel, or really out-of-touch. I was struck by people’s ability to adapt or react to personal events which later became symbols of a huge transformation within the country, like the MeToo movement. Are you going to push it under the table and hope it goes away? Or latch onto it, make it a force behind your work?

The story feels distinctly “New York”—not just in the art scene but in the day-to-day rhythms of the city. Mind you, this is said by someone who’s only visited a handful of times—but friends who lived in the city have regaled me with minuscule apartments, shared beds, and “signs you absolutely should not board certain train cars.” What elements of New York did you feel were essential to include in the novel?

That’s a huge compliment. I lived in New York for a short time while working at a couple of auction houses in my early 20s. I remember feeling very awed and horrified at the size and pace of things. The city sort of draws you out without your necessarily wanting to be drawn out. The towering buildings blocked out the sunlight, I was frightened by that. I based Rudolph partly on a guy I knew there. Pushy to the point of being superhuman, fast-talking, fast-walking, shoving people over—but also sort of oppressed. You feel very small compared to those buildings. They appear robotic, like humans aren’t meant to live in such conditions. I gave Ingrid my first apartment, which was this grim little basement with a window covered in pigeon droppings.

At the heart of the novel is the love story between art dealer Rudolph and gallery assistant Ingrid. Rudolph’s ruthlessness stands in stark contrast to Ingrid’s innocence. What is it about her that ultimately draws him in, and what does she see in him?

Their relationship was difficult to write. I think it’s largely physical. Rudolph is willing to do anything to get what he wants; Ingrid is not. People often want a border or someone to stop them from their worst impulses, or, alternatively, to push them closer to the person they secretly want to be. With Rudolph and Ingrid, I was thinking about how so many relationships are founded on fantasy. A dream of the other person. Power is attractive to young women, but also a sense that you can change things about this person. Conversely, people focused on their own ambitions often want someone who will devote themselves to them and believe in their dream as a fact. I saw Ingrid as someone who craved religion. Like an eighteenth-century nun in a way. Either you convert to the religion, or you gradually lose your hope, your belief, in a process of suffering.

In the beginning, Rudolph describes himself as a mole—burrowing under every hole in search of the next big deal for his clients. Yet, his office is perched at the top of a gallery, so that he’s also one with the birds. He seems like a chameleon, able to infiltrate any space. And people often see in him only the glittering façade he wants them to see. Does his character serve as a kind of mirror to the art world itself?

Definitely. In the art world I saw people become famous for a short time and then fade. All this frantic energy, the brevity of success, I channelled into Rudolph. There was a sense of a glittering object resting on a very fragile structure, like glass, which was about to shatter but just holding, for now. A downward spiral to me is always intriguing and fascinating to read about.

Greed and lust pulse through The Spectacle, and Rudolph suggests there’s something almost sexual in his clients’ possessive desire for the art they collect. Established artists form predatory relationships with their models and muses, and in one instance, a model uses her experience of exploitation to fuel her own art. This cycle of creation and consumption feels unsustainable. I’m curious—did you set out to explore this theme, or did it evolve as the story developed?

I didn’t consciously seek it out. It was happening all around me. I felt like a conduit, just recording things that were happening in the broader culture. Things like Harvey Weinstein, Trump’s locker room video, Jeffrey Epstein. At the same time the greed in the White House, the feeling of unbridled lust for cash and goods. Certain images appear in my head with connections that I don’t understand until later.

I thought a lot about what consumption and buying luxury goods meant in America. These middle-aged people who rise to a position of wealth and power and now something feels incomplete or missing. There’s a sexual component to acquiring it. I have the deepest compassion for that because I love shopping myself. Who knows what’s going on in these marriages, but I agree with Oscar Wilde on everything being about sex except sex, which is about power. MeToo was about power. Women’s art was getting more popular and there was enormous pressure to find hot women artists, create DEI policies, even as the political consensus reflected something menacingly different. I was interested in how this tension provoked a sort of frustrated hysteria on both sides.

We’re all about the thrills here at Thriller Thursday. What has thrilled you lately?

I loved Emma Cline’s The Guest. It’s a wonderful beach read that is also deeply poetic and well-written. Every scene feels sharp and precise but mysterious and true. That circle in the Hamptons is roughly the same as in The Spectacle, but she’s a much more accomplished stylist. It’s John Cheever meets Patricia Highsmith but make it 2024, which is my dream. I also loved Your Friends and Neighbors on Apple TV.

What are you currently reading?

Right now, I’m reading a collection of gothic stories for my second book, which is about a woman investigating the death of a famous confessional poet on Cape Cod. It’s called the Oxford Book of Gothic Tales.

The Spectacle sounds interesting! Thank you for this wonderful interview!

I was already interested in The Spectacle, and this fascinating interview just convinced me to buy. Thanks, Thriller Thursday!